By Josiah D. Walker

(This post was originally a paper written for the partial fulfillment of a Master’s degree at Gateway Seminary.)

INTRODUCTION

James instructs his readers to “Consider it a great joy […] whenever you experience various trials, because you know that the testing of your faith produces endurance.”[i] Charles Simeon must have taken this verse to heart. He withstood persecution that most of us would not be able to withstand. Not only did Simeon stand firm against persecution from his church members, but he also finished strong and endured until the end, having pastored at the same church, Trinity Church in Cambridge, England for 49 years.[ii]

John Piper describes Simeon as “a man who was a sinner like you and me, who was a pastor, and who, year after year, in his trials, ‘grew downward’ in humility and upward in his adoration of Christ, and who did not yield to bitterness or to the temptation to leave his charge – for 54 years.”[iii] In examining Simeon’s life, we see the selfless love that he had for Christ’s Bride, the church, despite the opposition and hatred that he endured; and as a result, we can learn how we too might love and serve Christ’s Bride faithfully as well.

THE BIOGRAPHY OF CHARLES SIMEON

Charles Simeon was born in 1759, a year after Jonathan Edwards’s death. He was born to a middle-class family and was the youngest of four brothers. Not much is known about his mother. His father was a non-believer and a well-off attorney. Growing up, Simeon attended The Royal College of Eton, a boarding school in England. After which, he went on to King’s College in Cambridge in 1779. There, he became a Fellow in 1782. The following year, he was ordained as a priest and appointed as vicar of Holy Trinity Church in Cambridge. Simeon served as the Pastor of Trinity Church for forty-nine years until his death in 1836. According to Arthur Bennett, By the end of his life, Simeon had become “the strongest religious influence in England.”[iv]

Charles Simeon lived a simple life. He never married and spent his life living in the rooms at King’s College in Cambridge, England. When Simeon’s brother left him a substantial amount of money after his death, Simeon turned it down and gave any extra income that he received to other religious and charitable organizations.[v]

CONVERSION STORY

Many people know exactly when they were ‘saved.’ Others would say that they have been saved on the ‘installment plan’ because they have seen, over a period of time, the moments when God was working in their life to regenerate their heart and turn it from a heart of stone and into a heart of flesh. For Simeon, salvation came slowly step-by-step during Passion Week in 1779 when he was asked by his Provost, William Cooke, to take part in the mid-week Lord’s Supper. Simeon was beside himself. It is said that when Simeon was faced with the thought of taking part of the Lord’s Supper, he found himself feeling like Satan was better equipped to take part in communion than he.

“In Passion Week,” writes Simeon regarding the time of his conversion, “as I was reading Bishop Wilson on the Lord’s Supper, I met with an expression to this effect — ‘That the Jews knew what they did, when they transferred their sin to the head of their offering.’”[vi] Leviticus 1:4 discusses the transfer of sin to make an acceptable substitute.

Simeon continued, “The thought came into my mind, what, may I transfer all my guilt to another? Has God provided an Offering for me, that I may lay my sins on His head? Then, God willing, I will not bear them on my own soul one moment longer.”[vii]

Although Simeon was reading about the Lord’s Supper, it was this Old Testament passage that God used to stir the man’s mind.

The thought stuck with Simeon. He continued, “Accordingly, I sought to lay my sins upon the sacred head of Jesus; and on the Wednesday began to have a hope of mercy; on the Thursday that hope increased; on the Friday and Saturday it became stronger; and on the Sunday morning, Easter-day, April 4, I awoke early with those words upon my heart and lips, ‘Jesus Christ is risen to-day! Hallelujah! Hallelujah!’”[viii]

While not a common evangelistic Scripture for Easter, Simeon’s encounter with substitutionary atonement in the Old Testament Law helped him take step after step until he found his hope and salvation in Jesus Christ. Simeon describes the fruit of his salvation encounter, writing, “From that hour peace flowed in rich abundance into my soul; and at the Lord’s Table in our Chapel, I had the sweetest access to God through my blessed Savior.”[ix]

PERSISTENCE IN THE FACE OF PERSECUTION

Charles Simeon was part of the Evangelical Party, which, like the Methodist Churches, “had been inspired by the preaching and example of John Wesley.”[x] In fact, Simeon became friends with John Wesley during the early days of his ministry.[xi]

Charles Simeon preached his first sermon at Trinity Church November 10th, 1782.[xii] It was his dream come true. He had long hoped to become the vicar of Trinity Church. For years he had petitioned God in prayer that he might be able to pastor there, as well as teach at the University.[xiii]

Unfortunately, that dream quickly darkened into a nightmare. Simeon had been appointed to the pastorate by Bishop Yorke; however, the congregation of Trinity Church had a different desire. They wanted the Assistant Curate at the time, Mr. Hammond, to be their pastor. In hearing this news, Simeon was willing to step down as vicar so the parishioners could have the pastor that they desired; however, Bishop Yorke told Simeon that even if he stepped down as vicar, the bishop would not appoint Hammond as the new vicar. Therefore, Simeon remained the pastor for fifty-four years. Ironically, it took almost that long for the congregation to come around to the idea of having him as their pastor.

Simeon faced ruthless opposition from his protesting parishioners. For the first five years of Simeon’s ministry, the congregation did not allow him to preach the Sunday afternoon service. Instead, they handed that service over to Mr. Hammond. Then after Hammond left, rather than relenting and allowing Simeon to preach, the church gave the service over to someone else for an additional seven years. It wasn’t until 1792, twelve years after joining Trinity church, that Charles Simeon was allowed to preach the afternoon sermon. If only that were where the conflict ended.

In addition to refusing to allow Simeon the opportunity to preach in the church that he pastored, the ‘pewholders’ of the church also locked the doors on their personal pews and would not allow anyone to sit in their pews. As a result, Simeon set up chairs in the aisles and surrounding areas of the church, only to have them thrown out onto the lawn.[xiv]

“For ten years, Simeon was harassed and persecuted at Trinity Church, Cambridge, by churchwardens and other church members who disliked having an Evangelical vicar.”[xv] Despite the on-slot of opposition that Simeon had endured for years, he continued faithfully preaching the Word and spending time in prayer, loving his congregation with patience and humility. Eventually, things relented, and Simeon enjoyed roughly thirty years of peace before more conflict would arise.

UNIVERSITY LIFE

According to Zabriskie, “Simeon’s basic contentions became permanently the major premises of the Evangelical movement largely because of the immense influence he exerted for half a century over the students at Cambridge, many of whom became the chief clerical and lay leaders in future years, and through the Simeon Trust, which he created.”[xvi] Part of the blessing of living at the University, was that Simeon was able to have ‘conversation parties’ on Friday nights. These weeknight gatherings were an opportunity to gather together with other students who had questions about spirituality and their faith. In the end, these parties resulted in “scores of young men becoming evangelical pastors and missionaries,” according to Gordon MacDonald.[xvii]

Simeon formed small groups long before today’s thinking of small groups ever existed. He also started Sunday School classes before the modern-day ‘Sunday School’ of the 1950s. In 1827, thanks to Simeon’s preaching, four students at the University organized a Sunday school for the less fortunate children in the area. The first week, 220 kids attended the class. It was soon known as “the Jesus Lane Sunday school”[xviii] This simple Sunday school class quickly resulted in other groups meeting, and in 1862 a Daily Prayer Meeting was started that drew a crowd of 10 students from the university. These prayer meetings included evangelistic messages, prayer, singing, and the reading of God’s Word. Fifteen years later, evangelical activity could be seen across Cambridge’s seventeen colleges and the Cambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union was formed to help students focus on missionary careers.[xix] The best part of it is this all started with just one man, Charles Simeon as there was no evangelical presence at Cambridge when Simeon started school there.

LEAVING A LEGACY

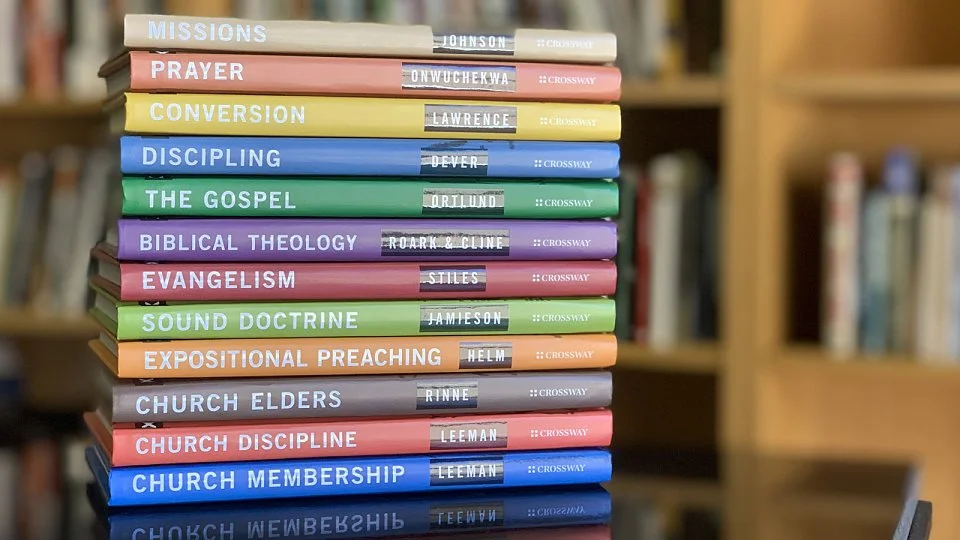

“When Simeon died in 1836, the city of Cambridge closed down and gave him the largest funeral people had ever known,” wrote MacDonald[xx] Simeon refused to get caught up in titles such as Arminian or Calvinist. His main objective was to teach and preach the gospel biblically. While Simeon was commonly referred to as a “Evangelical Calvinist” you can dig deeper into his theology by reviewing his collection of sermons in a 21-volume set which he completed in 1833 and gave to King William the Fourth.[xxi] Simeon was an advisor for the East India Company and a mentor for Henry Martin. Simeon had a heart for missions and was involved with various mission organizations such as the Foreign Bible Society and the Society for Promotion Christianity Among Jews. Simeon was also instrumental in the foundation of the Church Missionary Society.[xxii]

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM CHARLES SIMEON’S LIFE?

Examining the life of Charles Simeon, we see that Oswald Chambers was right when he said, “Prayer does not equip us for greater works--prayer is the greater work.”[xxiii]

Simeon made it a daily ritual to get up at 4:00AM each morning to read the Bible, study, and pray until 8:00AM.[xxiv] It was this practice that helped equip him for a lifetime of ministry. Simeon understood that prayer changes things. It changes us. He prayed intensely for those who opposed him. When newspapers slandered him, his response was: “I will pray for him” and when the churchwardens locked the church doors against him, he said “May God bless them with enlightening grace.”[xxv] It was common to find Simeon silently praying for others. Once, a German agnostic rode up to him on a horse and asked why Simeon’s lips were silently moving. His response was “I am praying for you, my friend.” In the end, their conversation that ensued led to the conversion of the German agnostic. Simeon’s life was grounded in prayer, and it showed.

Simeon faithfully served in ministry for over forty-nine years and overcome incredible hatred and opposition from not only his congregation but also the university where he taught at. He also conquered difficult health issues; through such adversity, we see that the keys to Simeon’s success came from God the Father. Simeon held fast to God’s Word. He was patient in tribulation and kind in persecution. He took James 1:3 to heart and lived it out each and every day. With laser focus, Simeon preached the redeeming message of the gospel everywhere he went. When faced with the opportunity to retire early and take it easy, Simeon hunkered down, and with his hand on the plow, continued to press forward in his kingdom work. When the time comes for the Lord to call us home, may the same words be said of us that are inscribed on the monument of Charles Simeon in Holy Trinity Church: “Determined not to know anything among you save Jesus Christ, and Him crucified.”[xxvi]

Bibliography

Christian Standard Bible (CSB) Nashville, Tenn.: Holman Bible Publishers.

Bennett, Arthur. Charles Simeon: Prince of Evangelicals. Evangelical Review of Theology 16, no. 2 (1992): 182–95.

Chambers, Oswald. My Utmost for His Highest. Grand Rapids, Mich: Discovery House Publishers, 1992.

Clayton, J F. 1936“The Centenary of Charles Simeon.” Modern Churchman 26 (9): 500–504. https://search-ebscohost-com.gbtssbc.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdar&AN=ATLA0001649916&site=ehost-live.

Hansen, Collin “Campus Ministry Cambridge Style” Worchester, Penn: Christian History Institute, 2005 Issue #88

MacDonald, Gordon “I Am Sim” Worchester, Penn: Christian History Institute, 2004, Issue 81.

Moule, M.C.G. “Charles Simeon”. London: InterVarsity Press, 1948.

Piper, John. 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018.

Zabriskie, Alexander C. “Charles Simeon: Anglican Evangelical.” Church History 9, no. 2 (1940): 103–19.

Endnotes

[i] James 1:2-3. Christian Standard Bible (CSB). All following scripture references will be taken from the CSB.

[ii] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 299.

[iii] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 320.

[iv] Bennett, Arthur. 1992. “Charles Simeon: Prince of Evangelicals.” Evangelical Review of Theology 16 (2): 182–95.

[v] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 317.

[vi] M.C.G. Moule, Charles Simeon (London: InterVarsity Press, 1948) 25-26.

[vii] M.C.G. Moule, Charles Simeon (London: InterVarsity Press, 1948) 25-26.

[viii] M.C.G. Moule, Charles Simeon (London: InterVarsity Press, 1948) 25-26.

[ix] M.C.G. Moule, Charles Simeon (London: InterVarsity Press, 1948) 25-26.

[x] Clayton, J F. 1936“The Centenary of Charles Simeon.” Modern Churchman 26 (9): 500–504. https://search-ebscohost-com.gbtssbc.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdar&AN=ATLA0001649916&site=ehost-live.

[xi] Clayton, J F. 1936“The Centenary of Charles Simeon.” Modern Churchman 26 (9): 500–504. https://search-ebscohost-com.gbtssbc.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdar&AN= ATLA0001649916&site=ehost-live.

[xii] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 304.

[xiii] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 309.

[xiv] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 310.

[xv] Clayton, J F. 1936 “The Centenary of Charles Simeon.” Modern Churchman 26 (9): 500–504. https://search-ebscohost-com.gbtssbc.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdar&AN=ATLA0001649916&site=ehost-live.

[xvi] Zabriskie, Alexander C. 1940. “Charles Simeon: Anglican Evangelical.” Church History 9 (2): 103–19.

[xvii] Gordon MacDonald, “I Am Sim” (Worchester, Penn: Christian History Institute, 2004), Issue 81, 50.

[xviii] Collin Hansen, “Campus Ministry Cambridge Style” (Worchester, Penn: Christian History Institute, 2005) Issue #88.

[xix] Collin Hansen, “Campus Ministry Cambridge Style” (Worchester, Penn: Christian History Institute, 2005) Issue #88.

[xx] Gordon MacDonald, “I Am Sim” (Worchester, Penn: Christian History Institute, 2004), Issue 81, 50.

[xxi] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 305-306.

[xxii] John Piper, 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful (Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2018), 304.

[xxiii] Oswald Chambers, My Utmost for His Highest (Grand Rapids, Mich: Discovery House Publishers, 1992) October 16.

[xxiv] Zabriskie, Alexander C. 1940. “Charles Simeon: Anglican Evangelical.” Church History 9 (2): 103–19.

[xxv] Bennett, Arthur. 1992. “Charles Simeon: Prince of Evangelicals.” Evangelical Review of Theology 16 (2): 182–95.

[xxvi] Clayton, J F. 1936 “The Centenary of Charles Simeon.” Modern Churchman 26 (9): 500–504. https://search-ebscohost-com.gbtssbc.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdar&AN=ATLA0001649916&site=ehost-live.