An Analysis of the Evidential Apologetic of Natural Theology

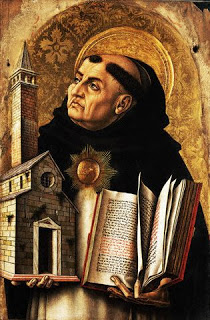

/ Introduction. Natural Theology, according to Walter Elwell, is the idea that “Truths about God [can] be learned from created things (nature, man, world) by reason alone.”[1] Thomas Aquinas championed this approach to recognize the existence of God as the Church encountered Jews, Muslims, and pagans that rejected the authority of Christian scripture.[2] John Calvin and other reformers, however, rejected Natural Theology in favor of initial enlightenment from the Holy Spirit.[3] In analyzing Natural Theology, this post will argue that a hybrid is necessary. While an evidential apologetic of Natural Theology creates a bridge from believers to unbelievers, it cannot be an effective method of apologetics or evangelism without a dependence upon both the Holy Spirit and Scripture.

Introduction. Natural Theology, according to Walter Elwell, is the idea that “Truths about God [can] be learned from created things (nature, man, world) by reason alone.”[1] Thomas Aquinas championed this approach to recognize the existence of God as the Church encountered Jews, Muslims, and pagans that rejected the authority of Christian scripture.[2] John Calvin and other reformers, however, rejected Natural Theology in favor of initial enlightenment from the Holy Spirit.[3] In analyzing Natural Theology, this post will argue that a hybrid is necessary. While an evidential apologetic of Natural Theology creates a bridge from believers to unbelievers, it cannot be an effective method of apologetics or evangelism without a dependence upon both the Holy Spirit and Scripture.Strength of Natural Theology: Its Necessity. Aquinas—potentially the father of Natural Theology—developed a process to argue in favor of the existence of God with the same scientific tools as Greek philosophy and logic; thereby, insisting that the Truths of God could be demonstrated by evidence found outside of Scripture.[4] Aquinas drew his support from Romans 1:20-21.[5] Of Natural Theology, Erickson writes, “It maintains not only that there is a valid revelation of God in such spheres as nature, history, and human personality, but that it is actually possible to gain some true knowledge of God from these spheres—in other words, to construct a natural theology apart from the Bible.”[6] The thrust, Erickson goes on to argue, is that it is possible to come to a knowledge of God without any authoritative writing or church body.[7]

Weakness of Natural Theology: No Dependence on the Holy Spirit and Scripture. While Aquinas used Romans 1:20-21 for support, many Protestant Reformers argue that the passage must be read in context, showing that “the pagan’s natural knowledge of God is distorted and turned only to his judgment.”[8] They find support in First Corinthians 2:14-16. Additionally, Erickson holds that Calvinists and Augustinians reject the assumption that, “Neither humanity’s natural limitations nor the effects of sin and the fall prevent humans from recognizing and correctly interpreting the Creator’s handiwork.”[9] Timothy Paul Jones, in summarizing John Calvin seems to agree with Erickson, arguing, “For Calvin, no one can, furthermore, begin to understand the Scriptures until the Holy Spirit enlightens him or her.”[10] Calvin, while not specifically arguing that the Scripture is a necessity for apologetics, demands that the Holy Spirit’s initial granting of faith most certainty is an essential requirement.[11]

Conclusion. No doubt, modern Natural Apologists like Norm Geisler, Ravi Zacharias, and Gary Habermas place their trust in the work of the Holy Spirit and in the authority of Scripture. Listening to and reading their work, one finds that Natural Theology is only the bridge to bring the unbeliever to hear the Word of God. Therefore, at the risk of oversimplification, a hybrid combination of both positions is reasonable when one accepts that Natural Theology is the tool used by the Holy Spirit. I do not believe than anyone can come to faith in Christ Jesus without the work of the Spirit and Scripture; however, any evidence suggesting otherwise is at least worth evaluating.

Bibliography

Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008.Elwell, Walter A. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker reference library. Grand Rapids,

Mich: Baker Academic, 2001.

Erickson, Millard J. Christian Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Book House, 1998.

Jones, Timothy Paul. “John Calvin and the Problem of Philosophical Apologetics.”

Perspectives in Religious Studies, 23 no 4 Wint 1996, p 387-403.

[1] Walter A. Elwell, Evangelical Dictionary of Theology (Baker reference library, Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2001), 815.

[2] Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Book House, 1998), 182.

[3] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008), 12-14, 26-29.

[4] Elwell, 816.

[5] Elwell, 816.

[6] Erickson, 181.

[7] Erickson, 181.

[8] Ewell, 816.

[9] Erickson, 181.

[10] Paul Timothy Jones, “John Calvin and the Problem of Philosophical Apologetics” Perspectives in Religious Studies, 23 no 4 Wint 1996, p 387-403, 398. (Jones’ use of the word “Scripture” is in relation to understanding anything about God.)

[11] Calvin, 26-29.

*This post was, in its entirety or in part, originally written in seminary in partial fulfillment of a M.Div. It may have been redacted or modified for this website.

** The painting depicting Thomas Aquinas was painted by Carlo Crivelli and is in the public domain.