Tongues: Viewed Through the Lens of Acts 2:1-21

/TONGUES:

AN ANALYSIS VIEWED THROUGH THE LENS OF ACTS 2:1-21

INTRODUCTION

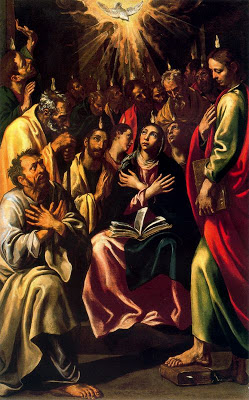

It was a day of great significance for the Church, for in the most practical sense, it was its inception. The Holy Spirit had come just as our resurrected Lord had promised. “But you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit,” said Jesus, “not many days from now.”[1] Pentecost. Luke’s narrative—recorded in the second chapter of Acts—has become the subject of many sermons, poems, paintings, and songs, but also church splits, uneasy parishioners, and theological overemphasis. The events of that day and others like it are at the root of a complicated and divisive practice in today’s Church referred to as “glossolalia,” “speaking in/with tongues,” or simply just “tongues.” Some churches have taken to understand this as a second baptismal experience, a necessary and required sign of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, a special “prayer language,” or some combination of the three. Debate circles around the nature of this language gift. Is it an earthly, know language, a language of angles, or something else? Is speaking in tongues a normative Christian experience? This post will certainly not end the debate, nor will it specifically address any events or experiences of tongues in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Instead, this paper will look at tongues as part of the coming of the Holy Spirit through the lens of Acts 2:1-13. (If you would like to read a more general theological look at the gift of tongues, please see "Tongues: A Spiritual Gift for Today?")

Through careful examination of Acts 2:1-13, one will see that at least some tongues uttered on Pentecost were not a prayer language, but rather, a witness of the mighty works of God uttered in a known language, or heard in the known language of the hearer. First, one must ask, “What happened on that day?” This post will attempt to answer this question through careful exegeses. Second, and effort to uncover the passage’s meaning will be offered, followed by Peter’s explanation given to the people seeking the meaning of that day. Then, once the lens has been established, this post will look through it to examine the other two tongues experiences in Acts and Paul’s teaching on the spiritual gift of tongues in First Corinthians 12-14. Before the conclusion of this post, a brief discussion about the other evidences of the power of the Holy Spirit’s coming will be offered.

PENTECOST: WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED? (ACTS 2:1-13)

Jesus had died on the cross, sending his followers into a tailspin until he appeared to them after his resurrection. Then Jesus spent forty days with his disciples, “speaking about the kingdom of God.”[2] And when he was finished, he ascended to heaven, but not before instructing the disciples to remain in Jerusalem to wait for the “promise of the Father.”[3] While they waited, the apostles and many others, about 120 in all, committed themselves to prayer in the upper room where they were staying.[4] They also filled the apostolic void left by Judas.[5] This brings the reader to the opening of Acts 2.

“When the day of Pentecost arrived, they were all together in one place.”[6] As Chapter 2 opens, Luke, the author of the book of Acts, transitions to the day of Pentecost. Bruce indicates that Pentecost, or “the day of the first fruits” occurred seven weeks or fifty days after Passover.[7] “Pentecost,” writes Bock, “was one of the three Jewish pilgrimage feasts to Jerusalem during the year, which explains why people from so many nationalities are present in verses 9-11.”[8] “They were all” most probably refers to the entire 120 and not just the Apostles that take center stage as the narrative advances.[9] And while there is reason to think the place they were all gathered is the upper room mentioned in Acts 1, the text does not clearly identify the location as such.[10] Stott even points out that Luke “is evidently not concerned to enlarge on this.”[11] Theories in scholarly circles suggest that this place is simply identified as a house, and according to Brock, “Luke always refers to the temple (twenty-two times) as [to hieron.”[12] The place, wherever it might have been, was likely a public place given that a crowd could hear the sound and quickly gather, as indicated in verse 5.

“And suddenly there came from heaven a sound like a mighty rushing wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting.”[13] Williams is quick to point out two significant aspects of verse 2: first, the sound came from heaven; and second the sound was “like” a mighty rushing wind. Given these two points, Williams concludes that this event was nothing but supernatural.[14] It is possible that it was this sound, and not the outburst of people speaking in tongues that served as the “sound” that attracted the attention of the multitudes in verse 5, however the text is not specific on this point. Taking liberty with the text, Calvin says of this moment, “The violence of the wind did serve to make them afraid; for we are never rightly prepared to receive the grace of God, unless the confidence (and boldness) of the flesh be tamed.”[15] And the fact that they were sitting leads Bruce to rule out that they were in the temple, lending more credibility that this event happened in a private residence as previously discussed.[16]

“And divided tongues as of fire appeared to them and rested on each one of them.”[17] The scholars are divided on the “tongues of fire.” Some look to symbolism, while others look to what the physical appearance might have been. Significantly, most positions agree that the tongues were distributed and rested on all the believers present, not just the Apostles. Just as with the wind, Williams points to the “as of” to show that these tongues of fire were not actual fiery tongues, but like tongues of fire, and clearly supernatural.[18] Additionally, Kistemaker demonstrates that the fire fulfills John the Baptist’s prophecy recorded in Matthew 3:11 and Luke 3:16, and, “fire is often a symbol of God’s presence in respect to holiness, judgment, and grace.”[19]

“And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance. Now there were dwelling in Jerusalem Jews, devout men from every nation under heaven. And at this sound the multitude came together, and they were bewildered, because each was hearing them speak in his own language. And they were amazed and astonished saying, ‘Are not all these who are speaking Galileans? And how is it that we hear each of us in his own native languages?”[20] This passage introduces the reader to “tongues,” and it very well could be that the Pentecostal dominations take the term “Spirit-filled” from this passage, although similar usages of “filled with the Spirit” appear through both the Old and the New Testaments. Writing about “filled,” Marshal states, “Luke uses the word fill to describe the experience. This word is used when people are given an initial endowment of the Spirit to fit them for God’s service (Acts 9:17; Luke 1:15) and also when they are inspired to make important utterances (Acts 4:8, 31; 13:9). . . .”[21]

The word, glossa, most commonly means either ‘tongue’ or ‘language,’ although Strong suggests that it “sometimes refers to the supernatural gift of tongues.”[22] Perschbacher expands on this meaning, adding that in reference to Acts 2:11, 1 Corinthians 13:1, and elsewhere, glossa might be thought of as, “a language not proper to a speaker, a gift or faculty of such language.”[23] On the other hand, Samarin, a linguist, defines glossa as “a single continuous act of glossolalia,” compounding the simple definition previously provided.[24] Under this definition, what then is glossolalia? It is worth noting that a cursory search of the Greek New Testament for the Greek word glossolalia—the combination of the Greek words glossa and (lalia), meaning “speech” or “way of speaking”—turns up no usage.[25] Glossolalia, as defined by Samarin, is first, “a vocal act believed by the speaker to be a language showing rudimentary language-like structure but no consistent word-meaning correspondences recognizable by either the speaker or hearers; (in Christianity) speech attributed to the Holy Spirit in languages unknown to the speaker and incomprehensible without divinely inspired interpretation”; and second, “(loosely) unintelligible speech, gibberish.”[26] This definition fails to see that the hearers in Acts 2 heard this glossolalia “in his own language,” suggesting that at least some of the hearers in Acts 2 understood what was being uttered.[27] While glossa is the word often used in association of the Spirit gift of tongues in the Bible, it is the word glossolalia that is the activity thought of when understanding ‘speaking in tongues’ in the charismatic and Pentecostal churches today. Against the idea of glossolalia, Grudem, seeking to define the common understanding (even if it may not be his own understanding) of ‘speaking in tongues,’ states, “Speaking in tongues is prayer or praise in syllables not understood by the speaker.”[28] Grudem’s definition however, does not leave room for the possibilities of other activities that could have been spoken in tongues seen in Acts and Corinthians, such as actual communication of prophecy to foreign listeners. It should also be noted that the use of the Greek word, dialektoo in verse 6 and the Greek word glossa used elsewhere in Acts 2 should draw no distinction; they are interchangeable in this usage.[29] Stott concludes, “that the miracle of Pentecost, although it may have included the substance of what the one hundred and twenty spoke (the wonders of God), was primarily the medium of their speech (foreign languages they had never learned).”[30] And Bock argues, “God is using for each group the most familiar linguistic means possible to make sure the message reaches to the audience in a form they can appreciate. Thus the miracle underscores the divine initiative in making possible the mission God has commissioned.”[31]

“ Parthians and Medes and Elamites and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabians—we hear them telling in our own tongues the mighty works of God. And all were amazed and perplexed, saying to one another, ‘What does this mean?’ But others mocking said ‘They are filled with new wine.’”[32] The list of nations provided by Luke gives the reader an idea of the native languages represented within the crowd, but Parsons suggests that this list is something more. According to Parsons, this list represents the various cultures and vast streams of tradition represented by within the Jewish people. And it is possible that the mission of the 70 (recorded in Luke 10) very well could have reached some, if not all, of these people groups; although this idea seems to have little to do with the narrative.[33] Brock’s idea that most of the people had come for the feast, lends support to Lea and Black's theory that visitors present on this day were responsible for founding the church in Rome, rather than missionaries sent out by Christ.[34]

Because some in the crowd thought the disciples were drunk, a few scholars suggest that not every disciple was speaking in a known language. However, Marshall points out, “. . . some people were ready to explain the speaking in tongues as a result of drunkenness; this would be a very natural explanation to offer if one heard people making unintelligible noises, as some of the sounds must have seemed to those of the hearers who did not recognize the particular language being used.”[35] Stott, in drawing differences between the events in Acts and Corinthians, suggests that the Holy Spirit was working in the hearers of the tongues, too.[36] This suggests that the tongues being spoken could have all be the same even, but the miraculous act of God was in the ear, not the mouth. Some also suggest that this moment signifies the reversal of the “curse of Babel.”[37] In trying to reconcile the tongues experiences in Acts and First Corinthians, scholars will often suggest that the “speaking in tongues” event in Acts 2 is somehow different than the “speaking in tongues” events elsewhere in the Bible. Lüdemann even goes so far as to suggest that tongues—as it is understood in First Corinthians—is the correct understanding of tongues and Luke simply misunderstood the Acts event.[38] Because the lens of this paper is Acts 2:1-13, little will be spend on this issue here; however, a brief discussion is offered in a later section.

ACTS 2:1-15: WHAT DOES THIS MEAN?

As the people of Jerusalem heard the sound like rushing wind and witnessed the Galilean disciples telling of the mighty works of God in their own tongues, they asked, “What does this mean?”[39] And as one can work to discover what happened on that day, the significance is found in finding its meaning. Tenney simply says, “This tremendous manifestation of divine power marked the beginning of the church,” but while this is correct, this certainly cannot be the only meaning of the events of Acts 2.[40] And what of tongues? White reminds his readers that the event of Pentecost and every similar event following a conversion is a fulfillment of the prophecy of both John the baptizer (Matthew 3:11-12, Luke 3:7-17) and Jesus Christ (Acts 1:5).[41] But is the meaning only about the fulfillment of prophecy? No. German explains that Jesus promised that a Comforter and Counselor would come after he was gone. That Counselor is, “the Spirit of truth, the Holy Spirit ([John] 14:26; 15:26; 16:5). The Holy Spirit will dwell in the believers (John 7:38, cf. 14:17), and will guide the disciples into all truth (16:13), teaching them ‘all things’ and bringing them ‘to remembrance of all that [Jesus] said’ to them (14:26). The Holy Spirit will testify about Jesus, as the disciples must also testify (John 15:26-27).”[42] This event, according to German, was the transition moment, when the Holy Spirit no longer influenced people (as he did in the Old Testament) but actually indwelled within the believer.[43] Erickson calls this, and the entire book of Acts, a “transition period,” ushered in with the events of Pentecost.[44] Duffield and Van Cleave interpret Acts 2 as something of an equipping for special service. They note that Jesus himself received the Holy Spirit before the start of his public ministry and Jesus’ expected even greater works from his disciples. The Holy Spirit was the necessary power needed for these ministries.[45] However, all of these theologians place little focus on the tongues, but instead on the coming of the Holy Spirit. Could this be because the meaning has little to do with the tongues

ACTS 2:14-21: PETER’S EXPLANATION

Despite what the various theologians might say about the meaning of Pentecost, Peter was the first believer to offer commentary.[46] He stood with the eleven and answered the peoples’ question, “What does this mean?” Peter recited Joel 2:28-32. “In the last days,” the Spirit would be poured out “on all flesh.”[47] This day, as Peter understood it, was the moment the Spirit was poured out and the first day of the “last days.” Peter lists some signs and wonders as he recites the passage from Joel. (It is worth noting that speaking in tongues is not specifically mentioned among these signs.) The “last days,” full of signs and wonders, will play out before the “great and magnificent day” when the Lord comes.[48] Joel may have been pointing to the first coming of Christ or the second, but surely, Peter is pointing to the second. “What does this mean?” Peter explains that this magnificent moment during Pentecost was the ringing in of the last days. A new era had begun; a corner had been turned. And to launch into his evangelistic message, Peter ends his recitation of Joel saying, “And it shall come to pass that everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord shall be saved.”[49]

What Peter does not discuss is the meaning of tongues. His explanation and sermon does not answer for us if tongues were (or are) a prayer language or a necessary sign of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. In fact, he does not say a word about the disciples speaking in tongues other than that they were not drunk because it was only the third hour of the day.[50] Why? Because the question, “What does this mean?” was not a question about the tongues. Because tongues were not the focal point of the coming of the Holy Spirit. Because most of the audience heard the disciples sharing the mighty works of God in their own native language. Because the tongues were a sign for the audience, significant enough that the people listened to Peter’s message. And because Peter was not focused on the signs, but on the gospel.

OTHER NEW TESTAMENT TONGUES EVENTS

With an understanding of what happened at Pentecost and its meaning, a cursory look at the other tongues events and teaching in the Bible—juxtaposing them against Acts 2—might provide insight on the topic of tongues on the day of Pentecost. This section is not meant to exegete each passage, or understand them for their stand-alone meaning, but to examine if the tongues as understood in Acts 2 works in agreement with the other tongues events.

ACTS 10:1-11:18. Luke records that Peter was in Joppa when he saw a vision. In this vision, God commanded Peter to “kill and eat” but the animals were unclean under the law.[51] Peter argues with God, but in the end submits. Just as this vision concludes, three men sent by Cornelius from Caesarea ask Peter to come back with them. Peter goes to Caesarea and meets with Cornelius, a devout and religious man who happens to be a Gentile. Peter begins sharing the gospel with Cornelius, and “While Peter was still saying these things, the Holy Spirit fell on all who heard the word.”[52] The Spirit had come to the Gentiles in Cornelius’ house. And they began “speaking in tongues and extolling God.”[53] When Peter reported to the other disciples in Jerusalem, he said, “As I began to speak, the Holy Spirit fell on them just as on us at the beginning.”[54]

If we look at this event through the lens of Acts 2:1-13, one should notice that there was no recorded rushing wind or tongues of fire. Although Peter says, “just as on us in the beginning,” he could be suggesting that the entire event was exactly the same; however, more likely, Peter is talking about the central event of the coming of the Holy Spirit.[55] The most obvious similarity is the presence of tongues. Here, there is no issue in assuming these tongues are like those of Acts 2, that is, that they are a known, earthly language and the words heard were praising God. Someone understood the language because Peter knew they were praising God. Stott calls this event in Caesarea the “Gentile Pentecost.”[56] Another alternative option for both this passage and Acts 2 is that the languages were unknown to all but that the give of interpretation was given to Peter or someone else in the group.

ACTS 19:1-7. Paul runs across twelve disciples who, it seems, either heard about Jesus before the coming of the Holy Spirit or heard about Jesus from someone who was not aware of the events at Pentecost. They were baptized into “John’s baptism,” that is, the baptism of repentance.[57] In fact, it is not even clear how much these men even knew of Jesus or the gospel. So Paul explains the complete gospel and they were re-baptized in the name of Jesus. Paul then lays his hands on them and the “Holy Spirit came on them, and they began speaking in tongues and prophesying.”[58] The use of the Greek word, “and” kai between “speaking in tongues” and “prophesying” in the Greek manuscripts leaves the door open to the possibilities that the prophesying might have been through their speaking in a tongue or in their native and ungifted language. However, juxtaposing this event with the other two in Acts, there is no reason to think that the tongues they spoke were not a known language, just is in Acts 2. Or it could be again, that the event included the gift of interpretation in conjunction with the coming of the Holy Spirit, but this is not explicitly mentioned. It is also interesting to see that in this event, there was a laying on of hands, unlike in the other events. If these men were not yet actually believers of Christ prior to meeting Paul, it could be seen that their conversion and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit were simultaneous or very close in time.

1 CORINTHIANS 12-14: PAUL’S TEACHING ON TONGUES. Reconciling the gift of tongues between the various passages in the book of Acts is nearly seamless; but reconciling Acts and First Corinthians is not as easy. Many pages on this topic are bound in the bindings of volumes of commentaries and theology books. Most conclude that the tongues in Corinth were different in some way than those spoken in Acts. Bruce for example, writes, “The glossolalia cultivated in the church of Corinth, to judge from Paul’s references to it (1 Cor. 14:2-23), had a different character: whereas the effect of the pentecostal glossolalia in Jerusalem was better understanding on the part of the hearers, the Corinthian glossolalia was unintelligible (except to the speaker) without an interpreter.”[59] Indeed, this may very well be the case, but viewing these differently is not the approach taken by this particular post. Instead, this post seeks to look at the tongues spoken in Corinth through the lens of those spoken in Acts 2:1-13 in an effort to understand those in Acts 2. Therefore, the conclusion that seems to reconcile Acts with First Corinthians is found not in the speaker of the tongue or in the tongues themselves, but in the hearer. Acts 2:8-11 demonstrates a wide variety of hears, each with their distinct native language, present to hear prophesy and praises of God in the other tongues. However, if a speaker was given the gift of tongues but the hearer does not understand that particular language, an interpreter would be necessary. While only speculation, it seems that the congregation in the Corinthian church, although likely diverse in languages, was unaware of the languages of the tongues being used; meaning such a sign and gift of tongues was of little value without an interpreter or one who naturally understood the language. Unintelligible babble would require instruction and restriction of its use to maintain proper order in the church services. First Corinthians 12-14 offers just such an instruction.

OTHER EVIDENCES OF THE HOLY SPIRIT IN ACTS 2

Often, the gift of tongues overshadows the other activities of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost. The most encouraging sign of the power of the Holy Spirit is seen in the radical change in the disciples. Duffield and Van Cleave write, “The disciples were transformed into different men after the Holy Spirit came upon them at Pentecost. In John 20:19 they are seen huddled together behind closed doors ‘for fear of the Jews.’ That very same group of men could not be kept behind closed doors after the Day of Pentecost (Acts 5:17-20), and they became as bold as lions before the Jewish authorities in the power of the Holy Spirit.”[60] The other evidence of the working of the Holy Spirit is found in verse 41 of the second chapter of Acts, which reads, “So those who received his word were baptized, and there were added that day about three thousand souls.”[61] Peter had concluded preaching his first sermon and 3,000 people gave their lives to Christ that single day, but this should only be credited to the work of the Holy Spirit. In addition, verse 43 indicates that the Apostles did many “signs and wonders,” and the last verse says, “And the Lord added to their number day by day those who were being saved.”[62]

CONCLUSION

As this post has attempted to demonstrate, careful examination of Acts 2:1-13, shows that at least some tongues uttered on Pentecost were not a prayer language, but rather, a witness of the mighty works of God uttered in a known language. It is most probable that all of the languages spoken through the gift of tongues were a known, earthly language, which would only seem like babble to one not recognizing the language. It is also possible that none of the spoken tongues were known but the hearers were gifted with the ability to hear in their native languages. In addition, this view is a workable explanation of all of the tongues in the New Testament, even if it is not popular. That being said, many other believers have come to different conclusions. Certainly, a careful exegesis of First Corinthians 12-14 to be used as a lens to evaluate the tongues experiences in Acts might prove helpful in seeing tongues in that light. (It is the hope of his author to someday do this work and post it here.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bock, Darrell L. Acts. Baker exegetical commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids,

Mich: Baker Academic, 2007.

Bruce, F. F. The Acts of the Apostles: The Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary. Grand

Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans, 1990.

Calvin, John. Calvin’s Commentaries, vol. 18. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Books, 2009.

Duffield, Guy P., and Nathaniel M. Van Cleave. Foundations of Pentecostal Theology. Los

Angles, Calif: Foursquare Media, 2008.

Elwell, Walter A. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker reference library. Grand Rapids,

Mich: Baker Academic, 2001.

Erickson, Millard J. Christian Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Book House, 1998.

Grudem, Wayne A. Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine. Grand Rapids:

Mich, Zondervan, 1994.

Kistemaker, Simon. Exposition of the Acts of the Apostles. New Testament commentary. Grand

Rapids, Mich: Baker Book House, 1990.

Lea, Thomas D., and David Alan Black. The New Testament: Its Background and Message.

Nashville, Tenn: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2003.

Lüdemann, Gerd. The Acts of the Apostles: What Really Happened in the Earliest Days of the

Church. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 2005.

Marshall, I. Howard. The Book of Acts: An Introduction and Commentary. The Tyndale New

Testament commentaries, 5. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 2002.

Parsons, Mikeal Carl. Acts. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2008.

Samarin, William J. Tongues of Men and Angels: The Religious Language of Pentecostalism.

New York: Macmillan, 1972.

Stott, John R. W. The Message of Acts: The Spirit, the Church & the World. The Bible speaks

today. Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press, 1994.

Strong, James, John R. Kohlenberger, and James A. Swanson. The Strongest Strong's Exhaustive

Concordance of the Bible. Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2001.

Williams, David John. Acts. New International biblical commentary, 5. Peabody, Mass:

Hendrickson Publishers, 1990.

[1] Acts 1:4b, ESV.

[2] Acts 1:3b, ESV.

[3] Acts 1:4, ESV.

[4] Acts 1:12-13.

[5] Acts 1:15-26.

[6] Acts 2:1, ESV.

[7] F. F. Bruce, The Acts of the Apostles: The Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary (Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans, 1990), 113.

[8] Darrell L. Bock, Acts, Baker exegetical commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2007), 95.

[9] Howard I. Marshall, The Book of Acts: An Introduction and Commentary, The Tyndale New Testament commentaries, 5 (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 2002), 68.

[10] Brock, 94.

[11] John R. Stott, The Message of Acts: The Spirit, the Church & the World, The Bible speaks today (Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press, 1994), 61.

[12] Brock, 94. This quote contains the Greek word, but for the sake of readers without the font, it has been removed from the statement.

[13] Acts 2:2, ESV.

[14] David J. Williams, Acts, New International biblical commentary, 5 (Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers, 1990), 40.

[15] John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentaries, vol. 18 (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Books, 2009), 74.

[16] Bruce, 114.

[17] Acts 2:3, ESV.

[18] Williams, 40.

[19] Simon Kistemaker, Exposition of the Acts of the Apostles, New Testament commentary (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Book House, 1990), 76.

[20] Acts 2:4-8, ESV.

[21] Marshall, 69.

[22] James Strong, John R. Kohlenberger, and James A. Swanson, The Strongest Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible (Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2001), 1599.

[23] Wesley J. Perschbacher, and George V. Wigram, The New Analytical Greek Lexicon (Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson, 1990), 81.

[24] William J. Samarin, Tongues of Men and Angles: The Religious Language of Pentecostalism (New York: Macmillan, 1972), xvii.

[25] James Strong, John R. Kohlenberger, and James A. Swanson, The Strongest Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible (Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2001), 1623.

[26] William J. Samarin, Tongues of Men and Angles: The Religious Language of Pentecostalism (New York: Macmillan, 1972), xvii. Italics added for emphasis.

[27] Acts 2:6.

[28] Wayne A. Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Mich, Zondervan, 1994), 1070.

[29] Bruce, 116.

[30] Stott, 66-67.

[31] Bock, 102.

[32] Acts 2:9-13.

[33] Mikeal C. Parsons, Acts (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2008), 39-40.

[34] Brock, 95. Lea, Thomas D., and David Alan Black, The New Testament: Its Background and Message ) Nashville, Tenn: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2003), 390-391.

[35] Marshal, 71.

[36] Stott, 65-66.

[37] For example, see Bruce, 119.

[38] Gerd Lüdemann, The Acts of the Apostles: What Really Happened in the Earliest Days of the Church (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 2005), 48-49.

[39] Acts 2:12b, ESV.

[40] Walter A. Elwell, Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, Baker reference library (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2001), 899.

[41] Elwell, 137.

[42] Elwell, 569.

[43] Elwell, 569.

[44] Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Book House, 1998), 894-895.

[45] Guy P. Duffield and Nathaniel M. Van Cleave, Foundations of Pentecostal Theology (Los Angles, Calif: Foursquare Media, 2008), 312-313. Incidentally, Duffield and Van Cleave also argue that this need for a “special power” is still relevant and necessary for ministry today.

[46] Technically speaking, the hearers of the tongues (including those accusing the disciples of drinking new wine) were the first to offer commentary.

[47] Joel 2:28, Acts 2:17, ESV.

[48] Joel 2:31, Acts 2:20, ESV.

[49] Joel 2:32, Acts 2:21, ESV.

[50] Acts 2:15.

[51] Acts 10:13b, ESV.

[52] Acts 10:44, ESV.

[53] Acts 10:46, ESV.

[54] Acts 10:15, ESV.

[55] Acts 10:15b, ESV.

[56] Stott, 196.

[57] Acts 19:3, ESV.

[58] Acts 19:6, ESV.

[59] Bruce, 115.

[60] Duffield, 313.

[61] Acts 2:41, ESV.

[62] Acts 2:47b, ESV.

*This post was, in its entirety or in part, originally written in seminary in partial fulfillment of a M.Div. It may have been redacted or modified for this website.

**The Photo is in the public domain.