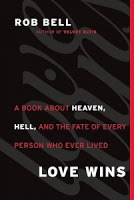

Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 7)

/

[This review is a review in parts. If you are just joining this review, start with "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Prolegomena)."]

The book is wrapping up. All those questions, it seems, will either be answered in the last two chapters or they will be left unanswered. The funnel is getting narrow and at some point everything needs to flow through.

Rob Bell's seventh chapter is titled, "The Good News is Better Than That." Going into the chapter, I was unsure if the Good News is better than the previous six chapters or better something new this chapter would present to its readers.

As I started the chapter, I found it thought provoking and enjoyable. Bell starts with a story of a woman who cuts herself (this idea is not enjoyable, but the point Bell is making is good). She dates men that hit her. Her life is hard and her understanding of love is a twisted mess. She's not really sure what love is so it is very difficult for her to understand the unconditional love God offers to her. She is faced with a choice between two realities--two stories. Her's or God's.

To understand how we see ourselves juxtaposed against how God sees us, Bell shifts to the parable of the prodigal son in Luke 15. Most of us know the story, but Bell presents it in a way that I have never seen before. He demonstrates that both the brothers have a story to tell. The story is their perspective of reality. They each tell their own story through warped lenses.

The younger son feels worthless as he comes home with his tail between his legs. He sees himself no more worthy than a hired hand on his father's property, if he's lucky. But the father has another story to tell about this son. It's a much different story. And the same is true of the older brother. Bell, seeing the contrast between what the boys believe about themselves and what the father has to say about them, says they have a choice to make. Which story will they believe? Bell writes,

But then things start to get squirrely. Bell uses this story to make his point about hell.

A parable is often Jesus' method of explaining something in a way that is memorable and easy to relate to. It is safe because people will either see a story about a farmer or virgins or brothers; or, if they are given sight, they will see a story about something so much more significant. But trouble comes when a student of the Bible tries to make the parable say more than Jesus intended for it to say. At times, we push parables too far. This seems like one of those times.

Following this discussion of how we see our selves in these two stories, Bell says, "The difference between the two stories is, after all, the difference between heaven . . . and hell" (169). For the next few pages, the question marks are put away and some serious statements about hell come out using this parable as a launching pad.

Bell writes, "Now most images and understandings people have of heaven and hell are conceived in terms of separation" (169). He goes on to provide some examples of these distinctions. Up and down. Two places far apart from each other. Here and over there. Interestingly, Bell fails to include the biblical parable of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke Chapter 16, where there is a great chasm fixed between one man and the other (Luke 16:26). Lazarus is at Abraham's side (or Abraham's bosom) and the rich man is in Hades. Separation.

In arguing against the idea of a separation (to include the image Jesus provides in his parable about Lazarus and the rich man), Bell writes,

Bell argues that "we create hell whenever we fail to trust God's retelling of our story" (173). "Hell," he writes, "is our refusal to trust God's retelling of our story" (170).

Are we really so powerful as to create hell? Do we really have that much control over God? The problem here, is that there are many people who feel that they understand God's love and God's justice better than God does. Maybe this is why the book has such an appeal with people--it allows them to feel justified in remaining in the driver's seat.

Bell then shifts to God's justice, or better put, to our understanding of God's justice. An example is given that if one has not accepted God in his lifetime and then dies in a car crash, God would have no choice but to send this person to an eternal conscious state of torment in hell. Bells says this god would instantly be different, like flipping a switch, and Bell can't accept that God might be like this. He argues that this would be unacceptable behavior for an earthly father implying that it is unaccetable for our Heavenly Father (174). Bell questions how a loving God who goes to extraordinary lengths to have a relationship with his creation could become so different and so mean in an instant (170-177). Does Rob Bell refuse to believe that this could be God. Is that option off the table? Or might it be that the understand of God before the car crash is not correct? Could Bell be unwilling to realize that God is who God is regardless of how Bell wants to create him? Maybe it could be that God's understanding of his story is so much better than our understanding, that we have a choice to accept God's story or our own. Bell continues, "Because if something is wrong with your God, if your God is loving one second and cruel the next, if your God will punish people for all eternity for sins committed in a few short years, no amount of clever marketing or compelling language or good music or great coffee will be able to disguise what one, true glaring, untenable unacceptable, awful reality" (175).

Standing on this foundation, the chapter moves through a series of statements. Still, no questions. Bell argues that God is about love, God is love. Interestingly, throughout most of this argument, God is made out to be void of justice. (Which if we argue away justice, there can be no grace.) Here is no balance.

He continually says "We shape our God, and then our God shapes us" (182, 183, and 184). I'm not sure I understand this statement. Bell seems to be implying that we actually can shape our God, but this only leaves me thinking about idol making and I'm not comfortable with that.

In addition, Bell spends a few pages attacking the Church again, or at least those among the Church who operate and believe differently than does Bell. He swings at those who present the gospel as a way "just to get into heaven" (179). Of these people he says, "An entrance understanding of the gospel rarely creates good art. Or innovation. Or a number of other things. It's a cheap view of the world, because it's a cheap view of God. It's a shriveled imagination. It's the gospel of goats" (179-180). He also attacks the understanding that "you're not doing enough" and he harps on ministry that leads to exhaustion and burnout. Yes, most of these statements are true in many ways; the gospel is more and better. Many would agree with Bell about some of his criticism of the Church today and some of these misunderstandings about the gospel; but the interesting thing is this: Bell fails to realize that he too is taking a stand, making a claim, and presenting a gospel. His position has its flaws and problems just as much as any other that he has problems with, maybe even more. But he doesn't seem to see this. Directed at them, he writes, "For some, the highest from of allegiance to their God is to attack, defame, and slander others who don't articulate matters of faith as they do" (183). Is this not a fair statement for Bell as well?

Throughout this chapter Bell makes some "very clear" statements, as he puts it (182). Good statements. "We do not need to be rescued from God. God is the one who rescues us from death, sin, and destruction. God is the rescuer" (182). Bell says the God forgives us "Before we could be good enough or right enough, before we could even believe in the right things" (189). On another page we find the statement, "It's only when you lose your life that you find it, Jesus says" (190). And, "Jesus meets and redeems us in all the ways we have it together and in all the ways we don't, in all the times we proudly display for the world our goodness, greatness, and rightness, and in all of the ways we fall flat on our faces" (190). The challenge however, is that through this chapter and most of the previous chapters, these statements are mixed with some rather problematic claims, assumptions, and passive allusions. There's a twist. We hear things that sound good, right, biblical, and we almost miss the twist. The next thing we know, we miss that there is a father running to his son, happy he has come home. Instead, we see a story of heaven and hell hanging out at a party together.

Up next, "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 8)," the final chapter.

* I have no material connection to Rob Bell or his book, Love Wins.

** Photo of son running to his father is by Sherif Salama and is registered under a creative commons license.

The book is wrapping up. All those questions, it seems, will either be answered in the last two chapters or they will be left unanswered. The funnel is getting narrow and at some point everything needs to flow through.

Rob Bell's seventh chapter is titled, "The Good News is Better Than That." Going into the chapter, I was unsure if the Good News is better than the previous six chapters or better something new this chapter would present to its readers.

As I started the chapter, I found it thought provoking and enjoyable. Bell starts with a story of a woman who cuts herself (this idea is not enjoyable, but the point Bell is making is good). She dates men that hit her. Her life is hard and her understanding of love is a twisted mess. She's not really sure what love is so it is very difficult for her to understand the unconditional love God offers to her. She is faced with a choice between two realities--two stories. Her's or God's.

To understand how we see ourselves juxtaposed against how God sees us, Bell shifts to the parable of the prodigal son in Luke 15. Most of us know the story, but Bell presents it in a way that I have never seen before. He demonstrates that both the brothers have a story to tell. The story is their perspective of reality. They each tell their own story through warped lenses.

The younger son feels worthless as he comes home with his tail between his legs. He sees himself no more worthy than a hired hand on his father's property, if he's lucky. But the father has another story to tell about this son. It's a much different story. And the same is true of the older brother. Bell, seeing the contrast between what the boys believe about themselves and what the father has to say about them, says they have a choice to make. Which story will they believe? Bell writes,

"The younger son has to decide whose version of his story he's going to trust: his or his father's. One in which he is no longer worthy to be called a son or one in which he's a robe-, ring-, and sandal-wearing son who was dead but is alive again, who was lost but has now been found. There are two versions of his story. His. And his father's" (165-166).What insight! As many times as I have read and studied this parable, I had never compared the two stories presented in each son. I've always seen only two stories when really there are four.

But then things start to get squirrely. Bell uses this story to make his point about hell.

A parable is often Jesus' method of explaining something in a way that is memorable and easy to relate to. It is safe because people will either see a story about a farmer or virgins or brothers; or, if they are given sight, they will see a story about something so much more significant. But trouble comes when a student of the Bible tries to make the parable say more than Jesus intended for it to say. At times, we push parables too far. This seems like one of those times.

Following this discussion of how we see our selves in these two stories, Bell says, "The difference between the two stories is, after all, the difference between heaven . . . and hell" (169). For the next few pages, the question marks are put away and some serious statements about hell come out using this parable as a launching pad.

Bell writes, "Now most images and understandings people have of heaven and hell are conceived in terms of separation" (169). He goes on to provide some examples of these distinctions. Up and down. Two places far apart from each other. Here and over there. Interestingly, Bell fails to include the biblical parable of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke Chapter 16, where there is a great chasm fixed between one man and the other (Luke 16:26). Lazarus is at Abraham's side (or Abraham's bosom) and the rich man is in Hades. Separation.

In arguing against the idea of a separation (to include the image Jesus provides in his parable about Lazarus and the rich man), Bell writes,

"This makes what Jesus does in his story about the man with two sons particularly compelling. Jesus puts the older brother right there at the party, but refusing to trust the father's version of his story. Refusing to join in the celebration. Hell is being at the party. That's what make is so hellish. It's not an image of separation, but one of integration. In this story, heaven and hell are within each other, intertwined, interwoven, bumping up against each other" (169-170).As I read Bell's argument, I have to wonder if this specific teaching was the purpose of Jesus' parable. I also wonder how this understanding of the parable fits within the rest of Jesus' teaching. I highly recommend reading the parable of the prodigal son again, but read in in light of the entire chapter. Could it be that this parable--coming right after two other parables about being lost and found--has something to do with the father's love more so than having to do with heaven and hell? And how does Bell's reading of the prodigal son parable line up with the parable of Lazarus and the rich man found in the very next chapter of Luke? I leave this for you to examine.

Bell argues that "we create hell whenever we fail to trust God's retelling of our story" (173). "Hell," he writes, "is our refusal to trust God's retelling of our story" (170).

Are we really so powerful as to create hell? Do we really have that much control over God? The problem here, is that there are many people who feel that they understand God's love and God's justice better than God does. Maybe this is why the book has such an appeal with people--it allows them to feel justified in remaining in the driver's seat.

Bell then shifts to God's justice, or better put, to our understanding of God's justice. An example is given that if one has not accepted God in his lifetime and then dies in a car crash, God would have no choice but to send this person to an eternal conscious state of torment in hell. Bells says this god would instantly be different, like flipping a switch, and Bell can't accept that God might be like this. He argues that this would be unacceptable behavior for an earthly father implying that it is unaccetable for our Heavenly Father (174). Bell questions how a loving God who goes to extraordinary lengths to have a relationship with his creation could become so different and so mean in an instant (170-177). Does Rob Bell refuse to believe that this could be God. Is that option off the table? Or might it be that the understand of God before the car crash is not correct? Could Bell be unwilling to realize that God is who God is regardless of how Bell wants to create him? Maybe it could be that God's understanding of his story is so much better than our understanding, that we have a choice to accept God's story or our own. Bell continues, "Because if something is wrong with your God, if your God is loving one second and cruel the next, if your God will punish people for all eternity for sins committed in a few short years, no amount of clever marketing or compelling language or good music or great coffee will be able to disguise what one, true glaring, untenable unacceptable, awful reality" (175).

Standing on this foundation, the chapter moves through a series of statements. Still, no questions. Bell argues that God is about love, God is love. Interestingly, throughout most of this argument, God is made out to be void of justice. (Which if we argue away justice, there can be no grace.) Here is no balance.

He continually says "We shape our God, and then our God shapes us" (182, 183, and 184). I'm not sure I understand this statement. Bell seems to be implying that we actually can shape our God, but this only leaves me thinking about idol making and I'm not comfortable with that.

In addition, Bell spends a few pages attacking the Church again, or at least those among the Church who operate and believe differently than does Bell. He swings at those who present the gospel as a way "just to get into heaven" (179). Of these people he says, "An entrance understanding of the gospel rarely creates good art. Or innovation. Or a number of other things. It's a cheap view of the world, because it's a cheap view of God. It's a shriveled imagination. It's the gospel of goats" (179-180). He also attacks the understanding that "you're not doing enough" and he harps on ministry that leads to exhaustion and burnout. Yes, most of these statements are true in many ways; the gospel is more and better. Many would agree with Bell about some of his criticism of the Church today and some of these misunderstandings about the gospel; but the interesting thing is this: Bell fails to realize that he too is taking a stand, making a claim, and presenting a gospel. His position has its flaws and problems just as much as any other that he has problems with, maybe even more. But he doesn't seem to see this. Directed at them, he writes, "For some, the highest from of allegiance to their God is to attack, defame, and slander others who don't articulate matters of faith as they do" (183). Is this not a fair statement for Bell as well?

Throughout this chapter Bell makes some "very clear" statements, as he puts it (182). Good statements. "We do not need to be rescued from God. God is the one who rescues us from death, sin, and destruction. God is the rescuer" (182). Bell says the God forgives us "Before we could be good enough or right enough, before we could even believe in the right things" (189). On another page we find the statement, "It's only when you lose your life that you find it, Jesus says" (190). And, "Jesus meets and redeems us in all the ways we have it together and in all the ways we don't, in all the times we proudly display for the world our goodness, greatness, and rightness, and in all of the ways we fall flat on our faces" (190). The challenge however, is that through this chapter and most of the previous chapters, these statements are mixed with some rather problematic claims, assumptions, and passive allusions. There's a twist. We hear things that sound good, right, biblical, and we almost miss the twist. The next thing we know, we miss that there is a father running to his son, happy he has come home. Instead, we see a story of heaven and hell hanging out at a party together.

Up next, "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 8)," the final chapter.

* I have no material connection to Rob Bell or his book, Love Wins.

** Photo of son running to his father is by Sherif Salama and is registered under a creative commons license.