Love Wins by Rob Bell (Conclusion)

/

[This review is a review in parts. If you are just joining this review, start with "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Prolegomena)."]

I've finished the book and my chapter-by-chapter review of Rob Bell's newest book, Love Wins. It feels like it has been a long journey, one that I now wish I had not set out on. It started when I watched a video of Bell promoting his book. Here's the video again:

I was intrigued, but then I stared thinking about how many people in my past would regularly bring up one of Bell's other books, especially Velvet Elvis. I remember watching as words Bell said in Velvet Elvis would be repeated, often with the echoing voice not even aware from where the information came. (I think I may have even done this a time or two.) But the challenge was that those of us repeating Bell never took the time to research the information, we just repeated it as fact. We thought Rob Bell was cool and therefore must be right. And looking back, I can see how what was often reverberated could have been a subtle twist on good information, skewing it to the point that it skipped beyond correct into the realm of just another twisted idea. And this is not just information on the latest music or directions to the subway station; this is information about God. This is information we must pray to get right! So with that in mind, I decided to read Bell's newest book, Love Wins and chronicle my journey. And as I have been on this journey, I have already heard multiple people echo ideas from Love Wins. I have received encouraging e-mails and positive comments, and I have also received the opposite. I've seen people both stand to support and attack to tear down Rob Bell--not his book or ideas, but the man himself. (And that's not really too productive, and yet that's the direction part of this conclusion must go.) I have no doubt that Bell will have an impact upon the American Church, for good and bad, for a long time to come.

What I found in Love Wins was more than 280 question marks. The book is only 198 pages and much of each page is consumed by blank space and large margins. I also found claims and counter claims. And I discovered an angry Rob Bell. From his book, he is clearly mad at the Church. He's critical of the Bride of Christ, but he makes his criticisms in such a way that he appeals to others who are also mad at the Church. From what he as written, he can't seem to understand or see why Jesus loves the Church. So it seems to me that Love Wins is not looking for God's way, but his own, so Bell can define what the Bible says and shape God into a god that he's comfortable with.

In the promotional video Bell asks if Gandhi is in hell. He asks if we can know for sure and if it is a person's duty to tell others. I find this interesting because Bell apparently feels that it is his duty (through the publication of his book) to tell his readers that we can't know where Gandhi is at the moment, but eventually he, like all people, will ultimately end up redeemed and in heaven. This appears an awful lot like universalism with Christ being the mechanism through which this happens.

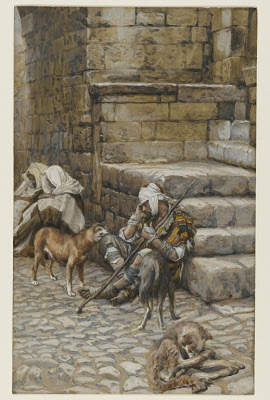

Another idea I found rather pervasive throughout the book is the sugar-coating of hell. It's a state of mind or an attitude or even the way a victim feels, but it's not an everlasting punishment according to Bell. It can't be according to his argument or nobody would like God. But in my opinion, that's really not how we should approach something so serious as God or hell.

Bell often seems to offer only partial information. There were places where he neglected a Greek word in his argument and it seems he often neglected the entire body and context of Scripture. If anything, it seems that Bell appeals to emotion and anecdotal examples. He builds a great argument through his very artistic writing style, but his argument usually starts on the wrong foundation. I found this rather problematic.

I kept waiting for Bell to answer some of his own questions. I was expecting him to act as an expert on "heaven and hell, and the fate of every person who ever lived," but in the end I didn't see it. I saw lots of questions and much criticism directed toward other Christians and what they are doing. I saw a man thinking out loud, and that is fine except his thoughts are finding their way in to places they aught not go until the thoughts have been fully developed.

All-in-all, I feel Bell failed to deliver on the claims he made about this book. And for that reason (among others addressed through out this chapter-by-chapter review), I would not recommend his book, Love Wins to anyone. My recommendation for anybody wanting to understand more about heaven and hell is the Bible. Pick it up and starting reading. It is THE SOURCE, not Rob Bell, not Bryan Catherman, not SaltyBeliever.com. Go to the source. Spend lots of time there. Read, study, learn, enjoy, and know God better. Love God more! That is the journey worth a lifetime.

If you're still with me though this lengthy review, thanks. May God bless you abundantly.

* I have no material connection to Rob Bell or his book, Love Wins.

I've finished the book and my chapter-by-chapter review of Rob Bell's newest book, Love Wins. It feels like it has been a long journey, one that I now wish I had not set out on. It started when I watched a video of Bell promoting his book. Here's the video again:

I was intrigued, but then I stared thinking about how many people in my past would regularly bring up one of Bell's other books, especially Velvet Elvis. I remember watching as words Bell said in Velvet Elvis would be repeated, often with the echoing voice not even aware from where the information came. (I think I may have even done this a time or two.) But the challenge was that those of us repeating Bell never took the time to research the information, we just repeated it as fact. We thought Rob Bell was cool and therefore must be right. And looking back, I can see how what was often reverberated could have been a subtle twist on good information, skewing it to the point that it skipped beyond correct into the realm of just another twisted idea. And this is not just information on the latest music or directions to the subway station; this is information about God. This is information we must pray to get right! So with that in mind, I decided to read Bell's newest book, Love Wins and chronicle my journey. And as I have been on this journey, I have already heard multiple people echo ideas from Love Wins. I have received encouraging e-mails and positive comments, and I have also received the opposite. I've seen people both stand to support and attack to tear down Rob Bell--not his book or ideas, but the man himself. (And that's not really too productive, and yet that's the direction part of this conclusion must go.) I have no doubt that Bell will have an impact upon the American Church, for good and bad, for a long time to come.

What I found in Love Wins was more than 280 question marks. The book is only 198 pages and much of each page is consumed by blank space and large margins. I also found claims and counter claims. And I discovered an angry Rob Bell. From his book, he is clearly mad at the Church. He's critical of the Bride of Christ, but he makes his criticisms in such a way that he appeals to others who are also mad at the Church. From what he as written, he can't seem to understand or see why Jesus loves the Church. So it seems to me that Love Wins is not looking for God's way, but his own, so Bell can define what the Bible says and shape God into a god that he's comfortable with.

In the promotional video Bell asks if Gandhi is in hell. He asks if we can know for sure and if it is a person's duty to tell others. I find this interesting because Bell apparently feels that it is his duty (through the publication of his book) to tell his readers that we can't know where Gandhi is at the moment, but eventually he, like all people, will ultimately end up redeemed and in heaven. This appears an awful lot like universalism with Christ being the mechanism through which this happens.

Another idea I found rather pervasive throughout the book is the sugar-coating of hell. It's a state of mind or an attitude or even the way a victim feels, but it's not an everlasting punishment according to Bell. It can't be according to his argument or nobody would like God. But in my opinion, that's really not how we should approach something so serious as God or hell.

Bell often seems to offer only partial information. There were places where he neglected a Greek word in his argument and it seems he often neglected the entire body and context of Scripture. If anything, it seems that Bell appeals to emotion and anecdotal examples. He builds a great argument through his very artistic writing style, but his argument usually starts on the wrong foundation. I found this rather problematic.

I kept waiting for Bell to answer some of his own questions. I was expecting him to act as an expert on "heaven and hell, and the fate of every person who ever lived," but in the end I didn't see it. I saw lots of questions and much criticism directed toward other Christians and what they are doing. I saw a man thinking out loud, and that is fine except his thoughts are finding their way in to places they aught not go until the thoughts have been fully developed.

All-in-all, I feel Bell failed to deliver on the claims he made about this book. And for that reason (among others addressed through out this chapter-by-chapter review), I would not recommend his book, Love Wins to anyone. My recommendation for anybody wanting to understand more about heaven and hell is the Bible. Pick it up and starting reading. It is THE SOURCE, not Rob Bell, not Bryan Catherman, not SaltyBeliever.com. Go to the source. Spend lots of time there. Read, study, learn, enjoy, and know God better. Love God more! That is the journey worth a lifetime.

If you're still with me though this lengthy review, thanks. May God bless you abundantly.

* I have no material connection to Rob Bell or his book, Love Wins.