Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 3)

/

[This review is a review in parts. If you are just joining this review, start with "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Prolegomena)."]

Rob Bell explores his thoughts about hell in the third chapter of his book, Love Wins. With a part of this chapter he challenges the traditional Christian view of a place of punishment, sorrow, and anguish, and it also seems that he is laying the ground work for a future argument about the everlasting aspects of the biblical hell. But Bell also uses this chapter to present an idea of hell on earth, maybe something like his ideas of heaven on earth. However, this twisted idea of hell that Bell shares speaks against the Gospel of Christ and against the biblical idea of hell; it is a heretical argument and a tragic concept with the potential for epic devastation, a message which no Christian preacher should ever suggest, preach, or teach.

Bell argues that hell on earth is for victims.

How can this be good news?

(At this point, I realize that readers who love and support Bell and his book will be tempted to stop reading this review, and that's okay. But it is my hope that those readers remember arguments that they themselves might have made. "Don't pass judgment," they might have argued, "and don't form an opinion until you've read the book." Some also argued that I would have to get to the end of the book to see the entire picture. So if this is you, I hope you continue reading this review. I hope you are willing to see it through to the end. I invite comments and questions via e-mail or in person. Please feel free to contact me. And I realize I have just leveled some serious claims about Bell's ideas; so Mr. Bell, I invite you to contact me to discuss your ideas so I can better understand. Come out to Salt Lake so we can discuss this over a cup of coffee.)

In this chapter, Bell shares some of his observations and experiences he has had as a pastor--a trip to Rwanda, a time sitting with a rape victim, a question from a boy about his father who had just committed suicide, the look of a cocaine addict, the ripples of a marital affair, and a cruel dead man.

When Bell was in Rwanda, he witnessed many teenagers missing hands and legs. They were victims of brutal treatment, forced upon them by no fault of their own. Bell says this was a tactic of a person's enemy. Cutting off your enemy's hand or leg leaves a brutal reminder of what you did to him. He is reminded of you every time he looks at his child. To this, Bells says, "Do I believe in a literal hell? Of course. Those aren't metaphorical missing arms and legs" (71).

Bell also asks if his readers have ever sat with a woman as she described what it was like when she was raped. In another question he asks, "How does a person describe what it's like to hear a five-year-old boy whose father has just committed suicide ask, 'When is daddy coming home?'" (71).

But here's the problem with these examples. In the common vernacular, one might suggest that a hot stone massage is "heavenly" or maybe it's a piece of chocolate cake the warrants such a high description. I even remember once buying a honey-baked ham from a company called Heavenly Ham, but I really don't think I bought a ham from heaven, not even heaven on earth. This is metaphorical hyperbole. Heaven is the greatest thing one can think of so we use it to describe great things, as if to say there is nothing better. But in reality, the biblical heaven is not a hot stone massage or a piece of cake or a ham or even the commercial building where I bought the ham. That's not what these kinds of statements are attempting to say. We use the word and idea of hell in much the same way. Hell is the worst thing we can think of so we make statements like, "War is hell." We want to dramatically declare that it just doesn't get any worse than this. So in that usage, armless, legless boys and rape victims and mothers who hear very difficult questions could easily say, "This is hell;" but that would not be the hell described in the bible.

What these horrific examples demonstrate is sin, or rather, the effects of sin. See, the teens in Rwanda and the raped woman are the victims of sinful acts thrust upon them. These are examples of sin in motion, the sin of humans; it's sin in the fallen world in which we live. However, in the model Bell gives us, Abel would have been in hell during the few moments while Cain was murdering him (Genesis 4). Stephen would have been in hell as he was being stoned to death, despite that the Bible says that he saw the heavens opened, and the Son of Man was standing at the right hand of God (Acts 7). In this model, it seems that the early Saints were passing into a hell on earth while Saul was ravishing the Church (Acts 8).

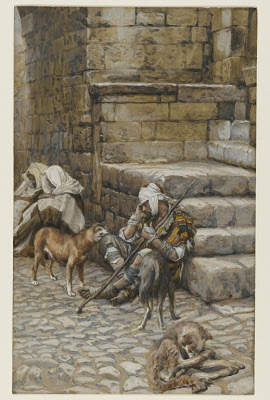

And let us take a look at a parable Jesus shared about a rich man who died and was in Hades. (Bell also examines this parable, but for a much different reason.) Luke 16:19-31 tells us a parable of this unnamed rich man and a poor begger named Lazarus. Lazarus sat out side the rich man's gates starving. Dogs licked Lazurus' sores, while the rich man did nothing for him. In the parable, Lazarus ends up in heaven while the rich man ends up in hell. There is a chasm between the two that does not allow anyone to pass from one place to the other (Luke 16:26). But looking through the paradigm Rob Bell is giving us, it seems that before the two died, Lazarus was in hell, not the rich man.

In this parable, the dead rich man calls out to Abraham (who is with Lazarus) for mercy, but Abraham reminds the suffering man, "Child, remember that you in your lifetime received the good things, and Lazarus in like manner bad things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish" (Luke 16:25, ESV). And even later, the rich man begs that his brothers be warned so that they may repent (Luke 16:30) and avoid this . . . this what? The rich man says "agony." Agony for what? Could it be punishment? But punishment for what? His sin. Maybe for neglecting the poor; maybe neglecting Jesus as Jesus discussed in Matthew 25 (another passage Bell examines for entirely different purposes in the previous chapter about heaven). Doesn't this make sense in light of Romans 6:23 which states that the wages of sin is death? Doesn't this make the gospel, that is, that Christ created a bridge across this chasm, seem like amazing news! The painting that was so frightful to Bell is the bridge, and the reason it is a cross is because that is how Jesus made the bridge.

As I thought about those Rwandan teens, I couldn't help but think about the people inflicting "hell" upon these children. They may have actually lived rather well, like the rich man. And what about the rapist? And what about the religious people who stoned Stephen to death? What about Saul? It doesn't seem that there was a punishment or agonizing hell on earth for them. Bell's hell on earth seems only to be agony and suffering for the victims. Does the Bible really teach that the victims suffer hell on earth, a biblical hell, for the sins committed against them? Or as with the rich man, does it seem that this judgment and punishment comes in the afterlife?

And what about the feelings and experiences of a cocaine addict or how the suffering a man might feel after he has sinned by having a marital affair? Has God cast any of these living people in to hell, or at least a hell on earth? (And again, we can't say Mahatma Gandhi is in hell but it's okay to declare that these living people could be in hell?) The answer is no, God has not cast these living people into hell on earth. For the victims, we might think of this suffering in light of 2 Corinthians 1:1-11 and Romans 8:28. These victims are not cast away from God. And for the perpetrators who are suffering as a result of their own sin, we might call this conviction in some cases, or it may be that the law is acting like a schoolmaster (Galatians 3), all for the benefit of their salvation. God may feel distant to them, but only because they have pushed him away, done as an act of their own self punishment. But God has not cast them to the burning trash heap of hell, not yet anyway. God is not neglecting them; he loves them and desires good things for them.

It may seem that the Bible only talks of hell as a garbage dump as Bell tries to present it. (He says that the only mention of hell is the Greek word gehenna. But even staying on the surface of semantics, this argument neglects 2 Peter 2:4's use of the word tartaroō.) And of course it would seem that there are very little mentions of hell or any kind of punishment if we only look for the word gehenna. And if we neglect Jesus' parables and much of the symbolic hints of punishment and reward, and even much of the direct statements about a punishment for sin after death, we might think that hell is not that big of a deal. We could falsely draw the conclusion that Jesus wasn't that concerned about hell. But that would be a mistake. Before you incorrectly draw that conclusion, read some passages in the Bible again, without anybody's commentary. Here are just a few examples; there are many more: Genesis 37:35; 42:38; 44:29, 31; Numbers 16:30, 33; Deuteronomy 32:22; 1 Samuel 2:6; 2 Samuel 22:6; 1 Kings 2:6, 9; Job 7:9; 11:8; 14:13; 17:13, 16; 21:13; 24:19; 26:6; Psalms 6:5; 9:17; Matthew 3:12; 5:22, 29–30; 7:23; 10:28; 11:23; 13:24-30, 42-43, 47-50; 16:18; 18:9; 23:15, 33; 25:32-33; Mark 9:43–47; Luke 3:17; 10:15; 12:5; 16:23; John 15:6; Acts 2:27, 31; James 3:6; 2 Peter 2:4; Revelation 1:18; 6:8; 9:2; 14:9-11; 18:8; 19:20; and 20:13–15

And I propose that if we are to look for any example of hell on earth we must look to the specific moment while Christ was on the cross as a propitiation for our sins; that is, taking on the sins of the world which were laid upon him (Isaiah 53:4-6; Romans 3:25; Hebrews 2:17; 1 John 2:2; 4:10). In that moment, when it appeared that Jesus was isolated from the Father, he cried out, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” which means "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" (Matthew 27:46, Mark 15:34). In that moment, Jesus was making a way for us. And if anything were going to make an argument for hell on earth, it must be this moment.

Next up, "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 4)."

* I have no material connection to Rob Bell or his book, Love Wins.

** Photo of "The Poor Lazarus at the Rich Man's Door" by James Joseph Jacques Tissot is used with permission from the Brooklyn Museum.